There’s an alarming paragraph near the end of the introduction of the 2018 National Defense Strategy Report, Providing for the Common Defense–The Assessment and Recommendations of the National Defense Strategy Commission. It’s a subsection entitled, “Civil-Military Relations.”

Civil-Military Relations

Constructive approaches to any of the foregoing issues must be rooted in healthy civil-military relations. Yet civilian voices have been relatively muted on issues at the center of U.S. defense and national security policy, undermining the concept of civilian control. The implementation of the NDS must feature empowered civilians fulfilling their statutory responsibilities, particularly regarding issues of force management. Put bluntly, allocating priority—and allocating forces—across theaters of warfare is not solely a military matter. It is an inherently political-military task, decision authority for which is the proper competency and responsibility of America’s civilian leaders. Unless global force management is nested under higher-order guidance from civilians, an effort to centralize defense direction under the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff may succeed operationally but produce profound strategic problems. It is critical that DOD—and Congress—reverse the unhealthy trend in which decision-making is drifting away from civilian leaders on issues of national importance.

This disturbing passage begins with a contrast: the imperative of healthy civil-military relations on the one hand and, on the other, the “relatively muted” civilian voices, undermining the concept of civilian control.” The commissioners are saying two things: 1) That our social and political structures require healthy control of the military by civilians, and, 2) there is an “unhealthy trend” towards “muted” civilian voices on national security matters.

There was concern about this potential tripwire back in the seventies, in a quiet debate about the pros and cons of going to an all-volunteer military and ditching the draft. Having a military caste evolve that would control the military separately from the civilian body politic was roughly how the danger was phrased. People like George McGovern cautioned that a separate class of Americans–the military–would arise and operate semi-autonomously, with a separate slate of priorities. National security and defense policy would drift irretrievably away from civilians and become the exclusive domain of the military caste.

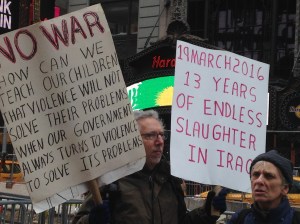

Thorny internecine conflicts would pit the civil and military classes against one another over issues of loyalty, patriotism and national security. The cliche of “supporting the troops” is one way we skip over the problem today and pass it on to the next generation of unprepared citizens. Much of the split consists of funding far flung military enterprises and foreign wars, especially when they enrich defense contractors at a cost to taxpayers and the civil needs of ordinary Americans. Think of the $1 million missiles we fire from drones in places like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, Sudan, Mali and Libya. Many, if not most, Americans in the civil society view these extra-judicial killings as illegal assassinations.

Our Constitution talks about belief in universal human rights, ones that our country is created to protect.

What we often overlook is that those rights are in the Constitution of the United States, not because Americans have special privileges, but rather because we believe every human being is entitled to these rights. That’s why the right to a trial by jury, the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and the right to bear arms are in the Constitution: because all people have such inalienable rights.

One of the revolutionary things about the 1787 Constitution of the United States is that human rights are no longer conditioned on a sovereign protector.

Our country is founded on the principle that everyone is free and has these rights without requiring a godfather, a warlord, or even a president to deem us worthy of the privileges of American citizenship. What may be getting lost in our militarized foreign policy is this spreading of the gospel of freedom through democratic participation.

It’s fine to go to Mexico, Central America, or even Iraq and Afghanistan to preach democracy and freedom. It seems hypocritical, though, when our foreign relations are really dictated by the financial interests of weapons makers and a pantheon of other military contractors and special interests.

We can’t spread democracy abroad by doing anything other than practicing democracy. Bombing, shooting, and propping up dictators is not democracy. Democracy demands debating, reasoning and compromising in good faith. A healthy democracy demands all citizens interact doing these things. That’s why we have endless wars. We’re committed to the war, not the democracy we pretend to nurture.

Fighting for peace doesn’t bring peace. It brings endless war. It may help bring a temporary slowdown, or even a truce. But those things don’t require any war at all. We’re free to endeavor to make peace any time with everyone who wants to join us in the democratic protection of our rights. War more likely sets in motion an explosive game of Whack-A-Mole.

Worse, the commissioners reviewing the National Defense Strategy don’t point out this contradiction. They see the problem as a struggle for power between institutions, even though they say, “civilians,” what they really mean is civilians in government jobs. They don’t highlight the difference between what the Constitution says and what all of us–as Americans citizens–do.

Implementation of the National Defense Strategy

According to the Commission, civilian control is being undermined.

The Commission is sounding an alarm that the national defense strategy is being implemented without sufficient civilian oversight.

Put bluntly, allocating priority—and allocating forces—across theaters of warfare is not solely a military matter. It is an inherently political- military task, decision authority for which is the proper competency and responsibility of America’s civilian leaders. — National Defense Strategy Commission, Providing For The Common Defense, U.S. Department of Defense, Washington, D.C., 2018, p. xi.